POTASSIUM (K)

Potassium is one of the essential elements for plants. It occurs naturally in most rocks and soils, but it must dissolve in water to be absorbed by plants. Potassium is required for plants to store nutrients—especially in fruit crops and root crops. Potassium fertilization supplements the potassium supplied from organic matter and the parent material in the soil. As a result, a mineral “reservoir” forms in the clay fraction and gradually supplies potassium to the soil solution as needed.

IMPORTANCE FOR PLANT LIFE

Potassium is one of the three primary nutrients required for field crops. Because it plays a role in stomatal regulation, it helps reduce plant water loss (transpiration) and thereby increases drought tolerance.

It regulates intracellular ion balance, supports carbohydrate formation in leaves, and facilitates the transport of these carbohydrates to storage organs (tubers, roots, and fruits). Potassium strengthens cell walls, improves resistance to lodging, and increases tolerance against diseases and pest attacks.

ABSORPTION MECHANISMS

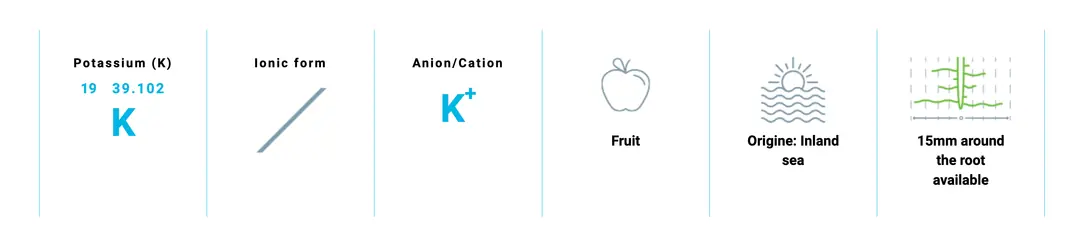

Potassium is absorbed by roots quite readily as K+ ions dissolved in the soil solution. It enters the plant passively with water in proportion to its concentration in the soil solution. It is also highly mobile within the plant and between cells.

INTERACTIONS AND DISTINCT CHARACTERISTICS

Plants often take up potassium without strict regulation; therefore, excess potassium is frequently released back into the soil environment through root exudates.

Soluble potassium that is available to crops in the soil solution is continuously replenished by the clay–humus complex. This replenishment depends strongly on soil moisture conditions (wet and dry phases) and seasonal climate. Because potassium must be dissolved in water, its availability declines rapidly under dry conditions; conversely, when water is excessive, potassium losses through leaching may increase.

CYCLE DIAGRAM

1. Animal wastes, plant residues, and other organic by-products originating from human activities are important sources of potassium as fertilizers.

2. Potassium is mostly mined in mixtures with sodium salts and sometimes magnesium salts. After refining, it is converted into potassium fertilizers suitable for agricultural use.

3. In soil, potassium occurs as the K+ cation within mineral structures, adsorbed on clay mineral surfaces, or dissolved in the soil water.

4. Leaching losses of dissolved potassium are more pronounced, especially in sandy soils with a low cation exchange capacity (CEC).

5. Surface runoff and erosion (potassium bound to solid particles) are also mechanisms that transport potassium out of fields.

6. Plant roots can take up potassium only in the form of dissolved K+ ions in the soil solution.

INDICATOR

In soil analyses, potassium is commonly measured as exchangeable potassium using extraction methods that are fairly consistent among laboratories. Interpretation is typically based on whether the measured potassium corresponds to about 4% of the soil’s cation exchange capacity (CEC). Therefore, to assess potassium supply accurately, the CEC value must also be known.

SENSITIVITY TABLE & SYMPTOMS

Potassium deficiency is observed first on older leaves. Yellowing of the leaf blade, followed by browning and tissue drying, and ultimately scorch-like necrotic areas along the leaf margins are typical symptoms.

EXCESS & REQUIREMENT

Excess potassium can negatively affect product quality; for example, it may lead to less extractable sugar in sugar beet and a lower dry matter content in potatoes.

Potassium excess may reduce magnesium uptake. At the same time, particularly when iron and manganese are not sufficiently available, it can also inhibit the uptake of these elements, leading to deficiency symptoms.

ORIGIN

Total potassium in soils is generally of magmatic origin (mica, potassium feldspar, etc.) and is trapped within parent rock particles. This geological potassium is released over time through weathering; however, the process is very slow and is not sufficient by itself to meet crop requirements.

Water-soluble potassium sources that can be used for fertilization are rarer; they are mainly found in ancient salt and sea deposits in Eastern Europe and North America. These deposits formed as water evaporated and precipitated salts, and were later covered by other sedimentary layers, protecting them from erosion.

These deposits contain sylvinite, a mixture of different water-soluble salts, primarily potassium chloride, sodium chloride, and magnesium salts. Through physical separation and refining processes, these mixtures are processed into potassium fertilizers suitable for agricultural use.

KEY FACTORS

SOIL CONTENT

Required potassium fertilization is calculated based on the amount removed by the crop and the level that must be maintained in the soil. More important than the absolute amount of extractable potassium is the percentage of K+ within the CEC. About 4% of the CEC in ionic form is generally considered sufficient. As CEC increases, the target potassium level in the soil also increases.

CLIMATE

Alternating wetting and drying cycles can promote the release of potassium from clay minerals and its replenishment in the soil solution. In contrast, prolonged excessive wetness or prolonged drought may hinder the release of potassium from the clay structure and its renewal in solution.

pH

pH does not directly affect potassium, but it can influence it indirectly through the quality of the clay–humus complex and the level of microbial activity. In soils with high microbial activity, more potassium is mineralized and transferred to the soil solution.

ANTAGONISM

Potassium has an antagonistic interaction with magnesium. The general binding priority on the clay complex is Ca > Mg > K > Na. Excess potassium can make it harder for magnesium (and partly other cations) to be retained and taken up by the plant.