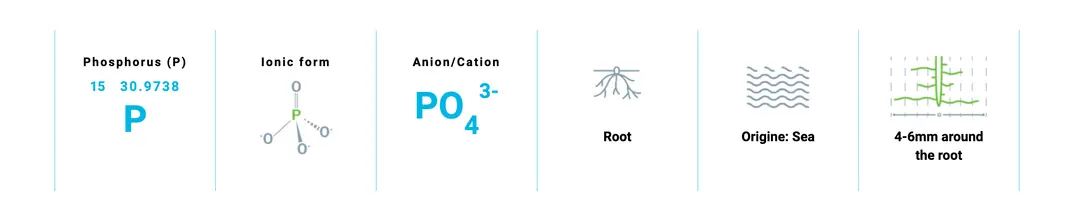

PHOSPHORUS (P) (P₂O₅)

Phosphorus is a vital element for plants and plays a critical role especially in root development and early growth stages. It supports essential processes such as energy transfer and photosynthesis, enabling plants to use nutrients more efficiently. Since phosphorus is generally immobile in the soil and can only be taken up by plants in limited amounts, supplementation through fertilization significantly improves yield and quality.

SENSITIVITY & SYMPTOMS

In phosphorus deficiency, young leaves may show purple-red discoloration and darkening on the leaf sheaths.

EXCESS & REQUIREMENT

Excess phosphorus in the soil can inhibit zinc uptake. In addition, if it is carried into waterways, it may create a risk of eutrophication.

ORIGIN

A small portion of phosphates is of magmatic origin; however, the vast majority comes from sedimentary phosphate deposits formed by the accumulation of marine microorganisms living in shallow seas.

KEY FACTORS

PHOSPHORUS IN THE SOIL

Identifying plant-available phosphorus in soil is difficult, which is why many analytical methods have been developed. Measuring phosphorus in a soil sample is the most accurate way to assess it.

ORGANIC MATTER

About 50% of phosphorus is in organic form. Organic matter mineralization increases phosphorus flow. By exchanging sites in binding zones (such as calcium), it can increase phosphorus availability.

TEXTURE

In clay soils, positively charged layers bind phosphate ions and reduce their movement. In sandy soils, diffusion is faster.

CLIMATE

Drought increases iron oxidation and thus increases phosphorus fixation. Low temperatures reduce biological activity, decreasing phosphorus availability. Best application period: late winter–early spring.

pH

In acidic soils, Al³⁺ and Fe³⁺ bind phosphorus; in alkaline soils, Ca²⁺ binds it. Ideal pH range: 6–7.

PHOSPHORUS USE EFFICIENCY

Only about 20% of the phosphorus applied with fertilizer can be used by the plant in that year. In calcareous soils, this rate is even lower. Precise dosing according to crop needs determines yield.