MOLYBDENUM (Mo)

Molybdenum availability differs from other trace elements because it depends on soil pH. It is not available in acidic soils, but becomes highly soluble and can be mobilized in alkaline soils. Required amounts are very low, so application requires precision and moderation.

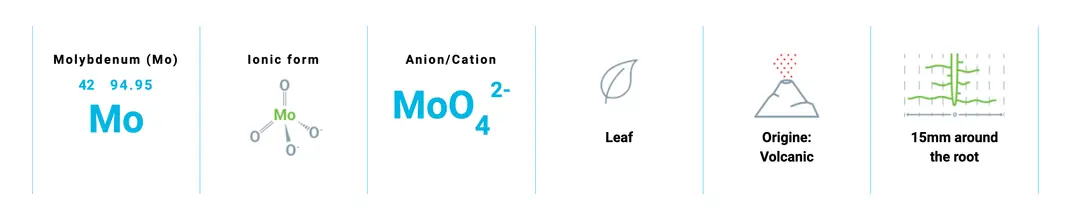

Mo

IMPORTANCE FOR PLANT LIFE

WHY IT MATTERS FOR THE PLANT

Molybdenum plays a role in enzymatic mechanisms related especially to nitrogen assimilation (nitrogenase and nitrate reductase). For this reason, it is one of the key elements that enables nitrogen to be converted into a form the plant can use.

UPTAKE MECHANISMS

Molybdenum is taken up by plants from the soil solution in anion form.

INTERACTIONS & SPECIAL FEATURES

Molybdenum works well together with phosphorus. Sulfur, on the other hand, can acidify the soil and reduce Mo availability.

MOLYBDENUM IN SOIL

Unlike other trace elements, molybdenum binds strongly to iron in acidic soils, so its availability is very low. As pH increases, molybdenum becomes more soluble and its availability to plants increases significantly.

Fresh organic matter inputs support Mo supply positively. However, peat develops under acidic conditions, so it does not provide the same benefit. When graphs showing Mo forms under different pH conditions are examined, it is seen that the MoO₄²⁻ form increases clearly as pH rises — and this is essentially the form taken up by plants.

SENSITIVITY TABLE & SYMPTOMS

Molybdenum deficiency is most often associated with nitrogen deficiency in legumes, because Mo is required for nitrogenase activity and N₂ fixation. In deficiency conditions, nitrogen deficiency symptoms may be observed.

In crucifers, grayish chlorotic patches can form between the veins, and leaf tissue may soften. Under severe deficiency, leaves can become completely deformed.

EXCESS & REQUIREMENT

Excess molybdenum can cause copper antagonism (Cu blockage) and may lead to deficiencies, especially in cereals and forage crops. Acidophilic plants (e.g., rubber) are sensitive to excess molybdenum.

ORIGIN

SOIL CONTENT

Molybdenum is not routinely analyzed in standard soil tests. Mo-poor and iron-rich soils are prone to Mo deficiency.

ORGANIC MATTER

Under low pH conditions, high organic matter content can reduce deficiency risk. Regular organic matter applications can supply soluble Mo. However, adding peat can cause Mo to be retained by humic acids — therefore reducing its availability.

CLIMATE

High temperatures above 25°C increase Mo solubility, while dry conditions reduce its availability.

pH

The most decisive factor for Mo uptake is pH. As pH increases, molybdenum becomes much more mobile.

INTERACTIONS WITH OTHER ELEMENTS

Phosphorus facilitates molybdenum uptake and transport. However, excess iron limits Mo uptake. Copper surplus or Cu applications can also reduce Mo absorption. Likewise, excessive manganese has a negative effect.

KEY FACTORS

The amount of Mo in soil can vary widely depending on parent material, iron content, and acidity level. In general, Mo is more available in alkaline soils, soils rich in organic matter, and young volcanic soils.

In iron-rich soils, Mo levels are generally low.