CALCIUM (Ca)

Calcium is an essential plant nutrient and helps neutralize soil acidity. It also acts as a flocculating agent, supporting soil structure stability and aggregation. In most soils, calcium is not a limiting nutrient; however, in certain crops it can be difficult to transport calcium within the plant—especially to reproductive organs.

Ca

IMPORTANCE FOR PLANT LIFE

Calcium is an essential element for building cell walls. It plays a major role in keeping fruits firm and extending their storage life. In most soils, calcium supply is not usually a problem; the main issue is transporting calcium to the plant parts that need it and ensuring it is available there in a usable form.

ABSORPTION MECHANISMS

Compared to other major nutrients such as nitrogen and potassium, calcium is more difficult for plants to take up. Its transport to high-demand areas— especially storage organs (for example, fruits and young tissues)—is limited; therefore, calcium deficiency can occur more easily in these organs.

INTERACTIONS AND DISTINCT FEATURES

In soil, calcium is a key driver of acid–base balance. By occupying exchange sites on the clay–humus complex in the right way, it creates a favorable environment for biological activity. It supports suitable conditions for microorganisms such as cellulose-degrading (cellulolytic) bacteria and nitrifying bacteria, and helps maintain a well-aggregated, well-aerated soil structure.

SOIL AND CYCLE SCHEME

Non-calcareous soils (those without calcium carbonate) naturally acidify over time; therefore, regular—but not excessive—liming is required. Typical calcium losses are about 100–400 kg CaO per hectare per year. In contrast, calcareous soils contain excess calcium and removing this surplus is not feasible. Under such conditions, special attention should be paid to the risk of trace elements (micronutrients) being fixed and becoming unavailable to plants.

CYCLE SCHEME

1. Recycling nutrients from manure, crop residues, and other organic by-products of human activities is an important fertilizer source, including calcium.

2. Calcium is extracted from quarries as calcium carbonate (limestone). It is crushed and ground to produce the basic liming materials used in agriculture. It can also be calcined in kilns to produce quicklime (calcium oxide), which is also used in agriculture.

3. In soil, calcium is continuously transformed between fixed, adsorbed, and dissolved forms.

4. Leaching of dissolved calcium into deeper layers with excess soil water must be considered when preparing a nutrient balance.

5. Surface runoff and erosion can also transport particle-bound calcium out of the field.

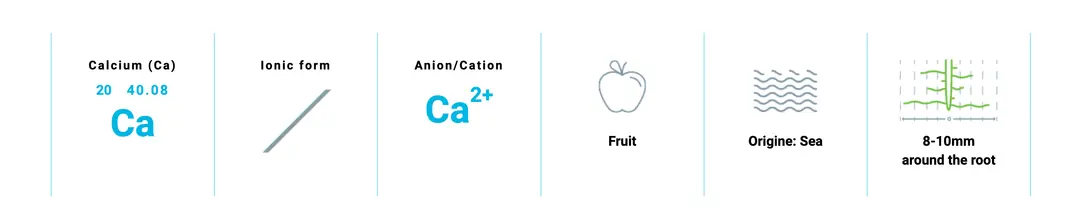

6. Plant roots can take up calcium only as dissolved Ca²⁺ ions in the soil solution.

INDICATOR

In soil tests, calcium is reported as exchangeable calcium measured with comparable extraction methods. Interpretation is made by evaluating the measured calcium level relative to the soil’s cation exchange capacity (CEC). The optimum level in ionic form is that at least 68% of the CEC is occupied by Ca²⁺. This stock is quite high compared to plant requirements and indicates a good calcium reserve in the soil.

SENSITIVITY TABLE & SYMPTOMS

Calcium deficiency in plants is relatively rare; it typically occurs in calcium-poor, acidic soils. It shows up as chlorosis (yellowing) in young leaves and fruits. For example, bitter pit in apples is a classic calcium deficiency symptom, appearing as bitter, corky spots on the fruit surface.

EXCESS & REQUIREMENT

Excess calcium is uncommon, but it can occur in calcareous (high-calcium) soils. An alkaline pH reduces the availability of phosphorus and certain micronutrients. Calcium can also form insoluble calcium phosphate compounds, thereby decreasing the amount of phosphorus available to the plant.

ORIGIN

Many calcium-rich soils are geologically derived from ancient seabeds. Calcium carbonate is either quarried as limestone and calcined at high temperatures to produce quicklime, or it is micronized finely enough (<150 μm) so that Ca²⁺ ions can diffuse into and saturate the clay–humus complex.

Geologically, calcium is often found together with magnesium. As a liming component, calcium acts both as a soil conditioner and as an important nutrient component of mineral fertilizers (for example, NAC 27 N).

KEY FACTORS

CALCIUM CONTENT IN SOIL

Soil calcium content (EDTA extraction) is evaluated together with the CEC value; it is desirable that more than 60% of the complex is occupied by Ca²⁺. In general, calcium levels between 2300–3300 ppm are considered satisfactory. Values below 1600 ppm are very low, while values above 5000–8000 ppm indicate calcium excess where antagonism must be managed.

TEXTURE

In loamy soils, calcium deficiency can impair both soil structure and fertility, leading to the loss of stable, well-formed aggregates.

pH

Soil pH (and any corrections) is not determined by calcium alone; however, calcium is the most commonly used exchangeable base for maintaining good soil fertility. Neutralizing value is usually calculated as a “CaO equivalent,” and the CaO requirement for pH correction depends both on the target approach to neutral pH and on the size of the clay–humus complex.

CLIMATE

Under moist conditions, calcium is generally less concentrated in the soil solution than under dry conditions. In other words, during rainy periods Ca²⁺ may be more dilute in solution, while in dry periods it may be more concentrated—affecting how calcium is supplied to the plant.